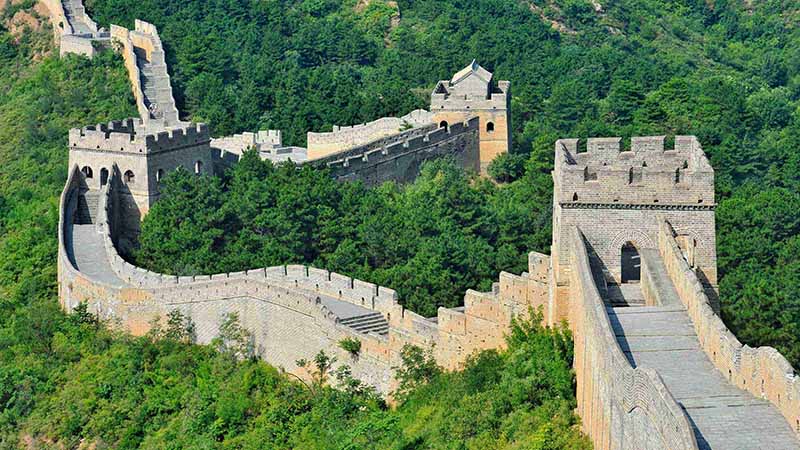

When people think of ancient China, the image that often springs to mind is the Great Wall of China, a landmark centuries-old wall snaking across rugged mountains, stretching towards the horizon. This isn’t just a feat of engineering; it’s a cultural symbol of ancient architecture, a living testament to the endurance and ingenuity of the Chinese people. Climbing its steps, especially at iconic spots like Mutianyu and Shanhai Pass, isn’t just about views or bucket lists—it’s about stepping into a story that began thousands of years ago.

A Brief Look Back in Time

The story of this wall has more twists than most novels. The earliest fragments go back as far as the 7th century BCE during the Warring States period. But the wall that most people recognise today began to take shape when Emperor Qin Shi Huang unified China in 221 BCE. He ordered the joining and extension of regional walls built by former state rulers to repel invasions from northern tribes.

Construction wasn’t a one-off project. Dynasties after Qin—like the Han (202 BCE–220 CE), Sui (581–618), and most famously, the Ming dynasty (1368–1644)—each took on the mammoth task of building, rebuilding, or reinforcing the wall. Under the Ming, fearing Mongol invasions, the wall became more than just tamped earth; it was reimagined with bricks, stones and watchtowers, much as we see it today.

The Stats: Bigger Than You Think

Let’s get into the numbers, because they may surprise you.

-

Overall Length: The State Administration of Cultural Heritage published a survey in 2012, announcing the wall and its branches total 21,196 kilometres. Yes, you read that right: over 21,000 km. That’s like walking the entire length of New Zealand almost twelve times.

-

Heights & Widths: In its best-preserved Ming era sections, walls average 6–7 metres high (nearly the height of a two-storey house) and 4–5 metres wide at the top. Towers can reach up to 12 metres.

-

Construction Materials: Early sections often used rammed earth, wood, and stone. The Ming upgraded this with kiln-fired bricks and huge stone blocks, hauling materials up steep slopes by sheer manpower.

-

Watchtowers & Fortresses: More than 25,000 watchtowers dot the wall, spaced so that signal fires or flags could alert soldiers to trouble—an ancient communication network.

Here’s a quick breakdown:

|

Dynasty |

Key Contribution |

Years Active |

|

Warring States |

Initial regional walls |

7th–4th centuries BCE |

|

Qin |

Linked walls, established core |

221–206 BCE |

|

Han |

Extended western sections |

202 BCE–220 CE |

|

Sui |

Repairs, modest extensions |

581–618 CE |

|

Ming |

Massive rebuilding, new towers |

1368–1644 CE |

Why Did They Build It?

The real purpose depended on who was calling the shots.

For early rulers, it was all about defence and protection. Nomadic groups from the vast steppes—Xiongnu, Mongols, and others—often raided border settlements. The wall wasn’t a magic shield, but it slowed down attacks, provided high-ground lookouts, and helped the military control border crossings.

Besides defence, the wall served as a sort of “customs line.” It played a crucial role in regulating trade along the Silk Road, taxing items moving in and out, and even keeping people from fleeing famines or conscription.

Yet, building and maintaining the Great Wall of China was hard labour—literally. Hundreds of thousands of workers, including soldiers, peasants, and prisoners, toiled on its stones. Many never returned home, and stories say the wall is held together by more than just bricks.

Mutianyu: Walk on History

Beijing’s sprawling suburbs slowly give way to green mountains, until suddenly, the wall appears—twisting, dipping and rising with the landscape like a giant stone dragon.

Mutianyu sits roughly 70 km northeast of central Beijing, praised as a landmark for its lush forest scenery and well-preserved battlements. Many locals and return travellers prefer Mutianyu over busier Badaling. Its 23 watchtowers in a 2.2 km section offer awe-inspiring perspectives, and the slopes feel much less crowded.

An added bonus: you don’t have to slog up endless steps if you don’t want to. Cable cars whisk visitors from the valley floor to the spine of the wall, giving sweeping mountain views. For families (or anyone like me who’s a bit of a kid at heart), the toboggan ride back down is a fun, fast memory-maker.

Locals in Beijing have their own saying: “Not been to the Great Wall, not a true hero.” And if you’ve only seen photos, climbing the Mutianyu steps, running your hands over stone blocks, and watching the wall unspool across mountain ridges, there’s a sense of quiet awe that’s impossible to fake.

Huanghuacheng: Where the Wall Meets Water

Just 60 km north of Beijing, Huanghuacheng offers one of the most unique Great Wall experiences—where history literally touches water. Here, the Ming-era wall plunges into a shimmering reservoir, its stonework half-submerged, creating mirror-like reflections that change with the light of day.

The name “Huanghuacheng” translates to “Yellow Flower City,” and in summer the surrounding hillsides erupt with golden wildflowers, turning the scene into something almost dreamlike. Unlike the more commercialised sections, Huanghuacheng feels serene, almost secret—perfect for travellers who want both history and a touch of romance.

Visitors can hike along restored battlements or simply relax by the lakeside, watching the wall stretch across ridges before dipping into the water again. At sunset, the glowing walls reflected on the reservoir create a surreal, cinematic moment—some even call it Beijing’s most picturesque Great Wall spot.

For couples, photographers, and anyone looking for a quieter, more poetic side of the Great Wall, Huanghuacheng is a must. It may not have the crowds of Badaling or the toboggan rides of Mutianyu, but its blend of water, stone, and wildflowers offers something truly unforgettable.

What You’ll See and Do

Despite its age, the wall is alive with things to notice.

-

Arrow slits, battlements, and parapets: These tell stories of tense border watch and conflict.

-

Watchtowers: Climb up and you’ll spot winding ribbons of wall fading into the mist.

-

Seasonal beauty: In April, cherry blossoms; in autumn, a riot of maple and oak colours.

-

Market stalls and food vendors: Perfect for trying candied fruit, fresh steamed buns, or a warming bowl of noodles.

Plan for a half-day; the air is clear, the pace is up to you, and each watchtower has its own character, providing historical protection and strategic vantage points. Don’t forget your camera—or some comfortable shoes.

Beyond the Wall: The Summer Palace

If you’ve journeyed out to Mutianyu or Huanghuacheng Water Great Wall in the morning, the Summer Palace can round off your day with peaceful lakes, intricate bridges, and lotus-filled gardens. During the late Qing dynasty the palace was the retreat of emperors needing a break from court drama.

You could spend hours exploring lush hills, man-made Kunming Lake with its dragon boats, and the Long Corridor (a 728-metre painted walkway filled with scenes from Chinese history and folklore). After conquering the steep steps of the wall, relaxing by willow-shaded waters is a perfect contrast.

A Map of Many Faces

The Great Wall isn’t a single endless barrier, much like the historic Silk Road, which was a network of trade routes. It’s more like a network of overlapping walls, spurs, trenches, and fortresses, extended or abandoned depending on the crisis of the day.

Key sections that draw visitors (and why):

-

Badaling: Closest to Beijing, busiest, excellent restoration.

-

Mutianyu: Scenic, fewer crowds, cable cars, toboggan.

-

Jinshanling & Simatai: Rugged, wild, preferred by experienced hikers.

-

Jiayuguan: The “end of the wall” in Gansu Province; a key point along the silk road, and desert and oasis crossroads.

-

Huanghuacheng Water Great Wall: Unique lakeside section where parts of the wall are submerged; known for summer wildflowers and tranquil scenery.

If you glance at a map, you’ll see that the wall zigzags, splits, and sometimes just peters out amid sand dunes, mountains, or farmland, with historic sections like Shanhai Pass marking significant transitions. Archaeologists are still rediscovering forgotten branches every few years.

Food, Family and Culture

Any trip to the Great Wall is about more than stones and stories. It’s also a meeting place for cultures and traditions. Street-side snacks like jianbing (savoury pancakes) or skewered lamb hint at centuries of trade between Han Chinese, Mongols, Manchus, and Uighurs.

For families travelling with kids, it’s not just an active day out, but a living lesson in technology, teamwork, and tenacity. Bring plenty of water, allow time for rest and photos, and don’t rush the experience—even if little legs get tired!

Three Bears Travel, being a family business, approaches every trip with the perspective that travel is about building memories together. After years spent living and working in China, we see the wall not as a monument, but as an ongoing link to stories of hardship, resilience, and community.

Making the Most of Your Visit

Here are some handy tips:

-

Best times to visit: Weekdays, early mornings, and autumn months (September–November) bring the smallest crowds and the best weather.

-

What to pack: Sunblock, snacks, a hat, and sturdy shoes. Spring and autumn can mean cool mornings and hot afternoons.

-

Accessibility: Mutianyu is more accessible for children and older travellers, mostly thanks to the cable car and reasonably gentle walks.

-

Language: While signs are in both Chinese and English, having a phrasebook or translation app can help with local food stalls or taxis.

Legends and Stories

The folk tales are as rich as the scenery. One of the best-known is the story of Meng Jiangnu, whose husband died building the wall. Her tears (according to legend) caused a section to collapse, becoming a symbol of love and loss.

Others say the wall can be seen from the moon, but that’s just a myth—though at over 20,000 km, it’s plenty remarkable from the ground!

The Wall Today

In modern times, large sections of the Great Wall of China have weathered, eroded, or crumbled, battered by wind and, in some cases, old bricks repurposed for village homes. Less than 10% of the original wall remains in good condition.

Conservation efforts continue, with a view to balance history, the environment, and the flood of tourists drawn from every corner of the globe.

Stepping along its stone spine, you’re treading a link between dynasties and dreams, emperors and everyday people. Whether it’s the thrill of finally seeing that zigzag silhouette for yourself or sharing a moment over hot noodles and local beer, memories of the Wall linger long after the dust settles from your shoes.

Want more China travel itineraries? Click here!

If you have any other questions, feel free to click here and get in touch with us.

If you need a personalized travel plan, feel free to click here and let us help you.